The United States taxes its citizens, resident corporations and tax residents on a worldwide income basis. U.S. taxpayers who have cross-border business operations often find themselves caught up in a net of complicated international tax rules, both in the U.S. and in the country where they want to operate. Beyond the sheer complexity of these rules, U.S. taxpayers also must worry about cumbersome reporting requirements because of these rules.

This article will explain the common entity structures that U.S. taxpayers should consider when establishing non-U.S. business operations.

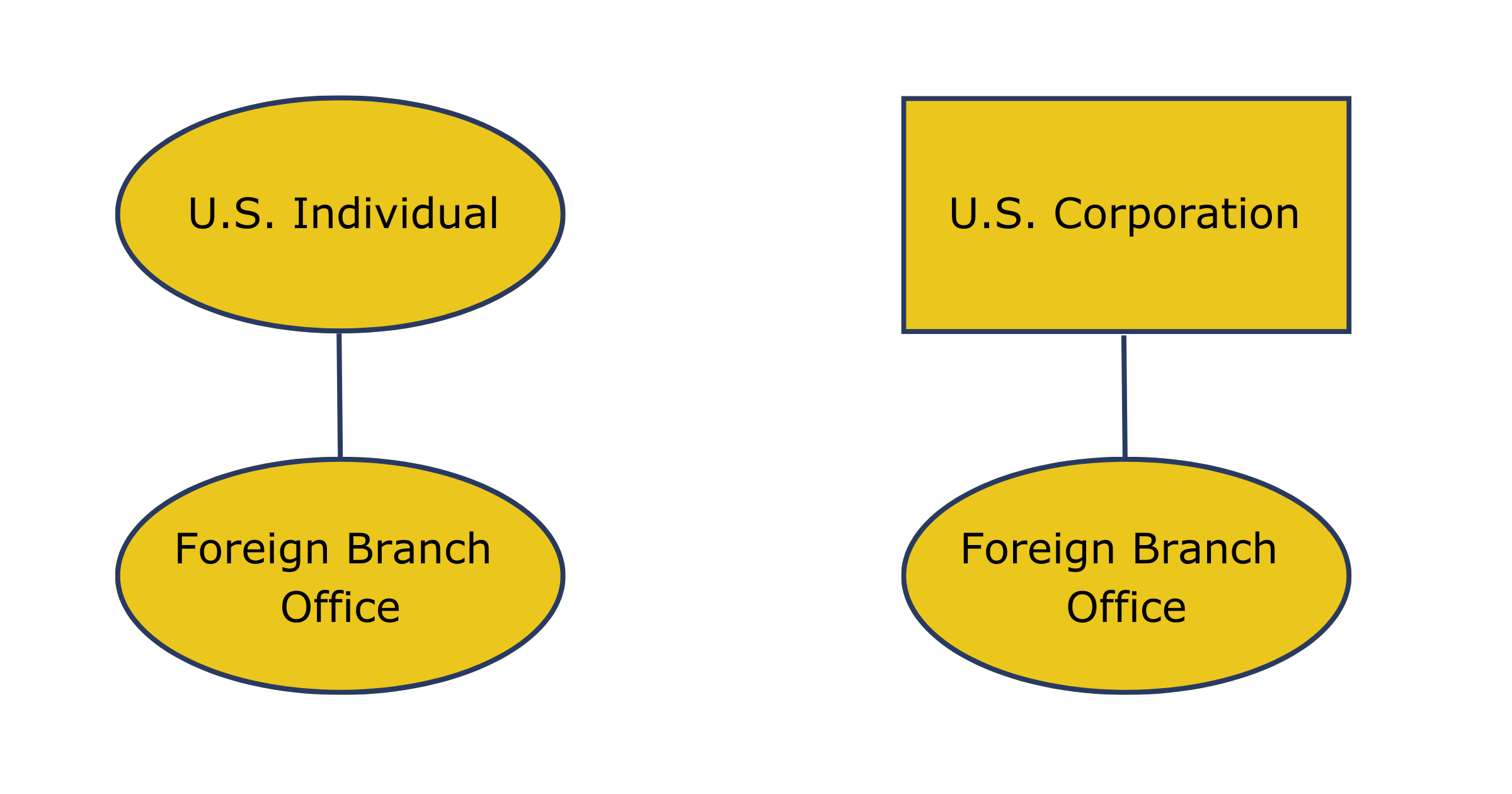

FOREIGN BRANCH

Having an unincorporated foreign branch office may seem like the most straightforward and flexible way to start and operate a business in a foreign country from an administrative perspective, especially in the early stages of establishing a business presence abroad. One of the main benefits is that the U.S. taxpayer can conduct business in the foreign country without setting up a legal entity, making this the least complex of the available options.

In general, owning a foreign branch will result in the income earned by the foreign branch flowing through to the U.S. taxpayer. If the U.S. taxpayer is an individual, the foreign income will be taxed at individual tax rates. If the U.S. taxpayer is a corporation, the income of the foreign branch will be subject to the U.S. corporate tax rate of 21 percent. To the extent that the foreign branch pays income taxes in the foreign country, the U.S. taxpayer is allowed to credit those foreign taxes against U.S. federal tax on the foreign branch income, subject to certain limitations.

- Distributions: Distributions from a branch are disregarded and therefore mostly tax-free to the U.S. owner, although the U.S. owner might need to recognize and pay tax on foreign exchange gain or loss on distributions.

- Tax Compliance: The U.S. tax compliance for a foreign branch is simple. The U.S. taxpayer must file Form 8858 every year with their federal income tax return. The form only requires the reporting of a high-level summary of the income statement and the balance sheet. Therefore, a foreign branch often requires less burdensome filing requirements for the U.S. owner.

- Other Considerations: A foreign branch is straightforward to establish, but it is not always the most tax-efficient choice. U.S.-parented groups often prefer having a legal entity in a foreign country for legal and operational reasons. For this reason, it is not very common for a U.S. taxpayer to operate as a branch office in a foreign country.

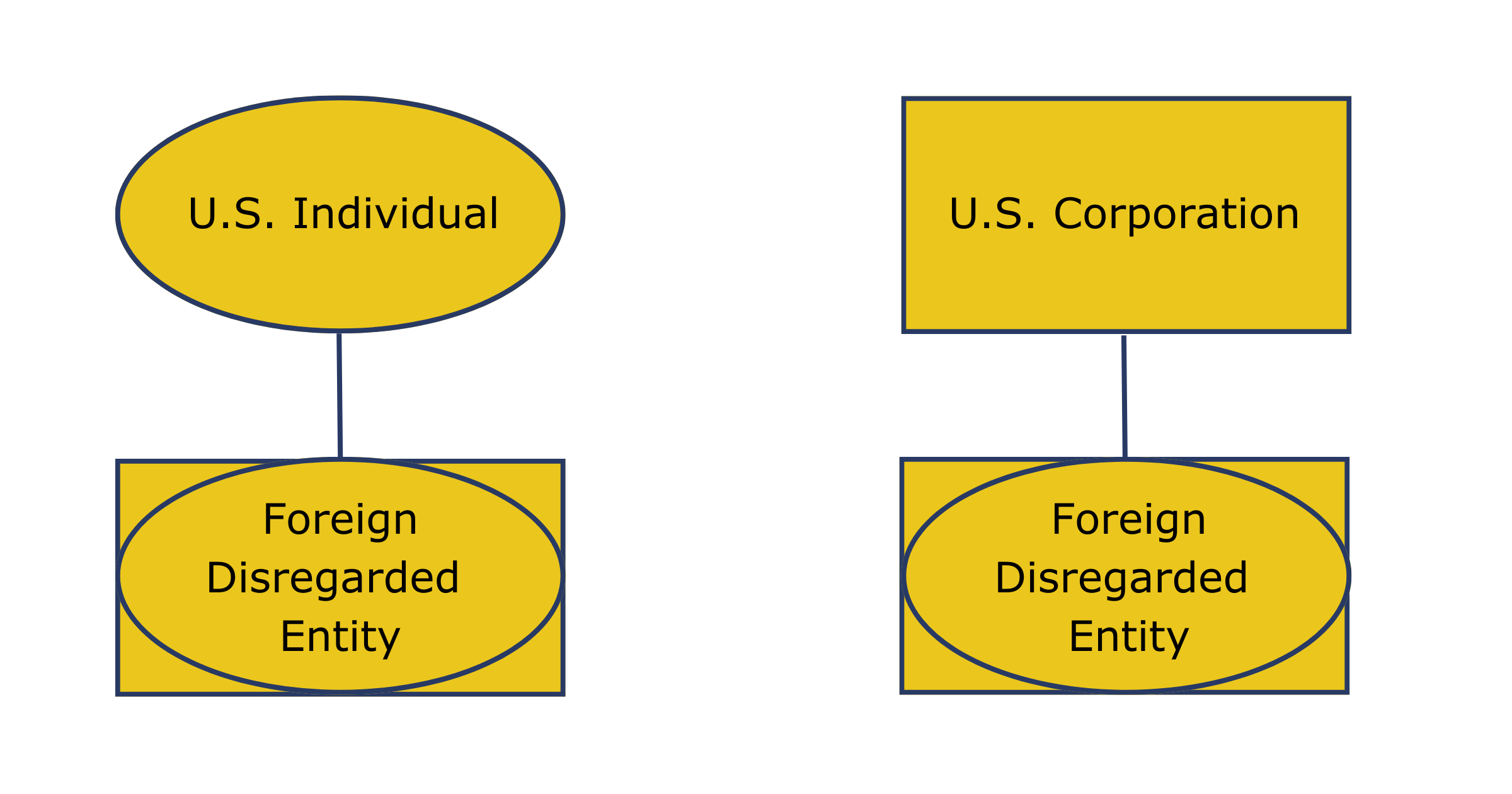

FOREIGN DISREGARDED ENTITY

The U.S. parent company might prefer to have a legal entity in the foreign country for legal or other reasons. From a U.S. tax perspective, however, the U.S. parent company may still prefer to treat the foreign business as a branch.

Certain types of legal entities organized under the laws of a foreign country that have one single owner may elect to be treated as a foreign disregarded entity (FDE) to make this possible. This is commonly known as the check-the-box (CTB) election. An FDE is viewed as a legal entity from a local tax and legal perspective but is disregarded for U.S. federal income tax purposes. In other words, the U.S. taxes the entity similarly to a foreign branch, but the owner can still enjoy the advantages of having a separate legal entity in the foreign country.

- Distributions: Distributions from the FDE to its owner are disregarded in the U.S. Like a foreign branch, the U.S. owner may still need to recognize foreign exchange gain or loss on distributions from the FDE. Please note that distributions from an FDE may often be taxable in the local country, subject to withholding taxes.

- Tax Compliance: The annual U.S. tax compliance for an FDE is the same as that for a foreign branch. The U.S. taxpayer must file Form 8858 every year with their federal income tax return. The form only requires the reporting of a high-level summary of the income statement and the balance sheet.

- Other Considerations: It is important to note that an FDE is a hybrid entity; it is treated as a legal entity locally, but as a pass-through entity in the U.S. When viewed in isolation, transactions involving hybrid entities can lead to distortions with respect to the taxation of transactions between those entities in the U.S. and abroad. To address such distortions, both the U.S. and many foreign countries have enacted anti-hybrid rules that may unilaterally deny tax deductions, depending on the transactions and types of entities involved. The U.S. dual consolidated loss (DCL) rules are an example of anti-hybrid rules that the U.S. has in place, with the principal purpose of preventing corporate taxpayers from claiming a loss deduction in multiple countries. Therefore, a detailed analysis of any material intercompany payment flows involving FDEs is advisable to prevent the denial of local deductions under applicable anti-hybrid rules.

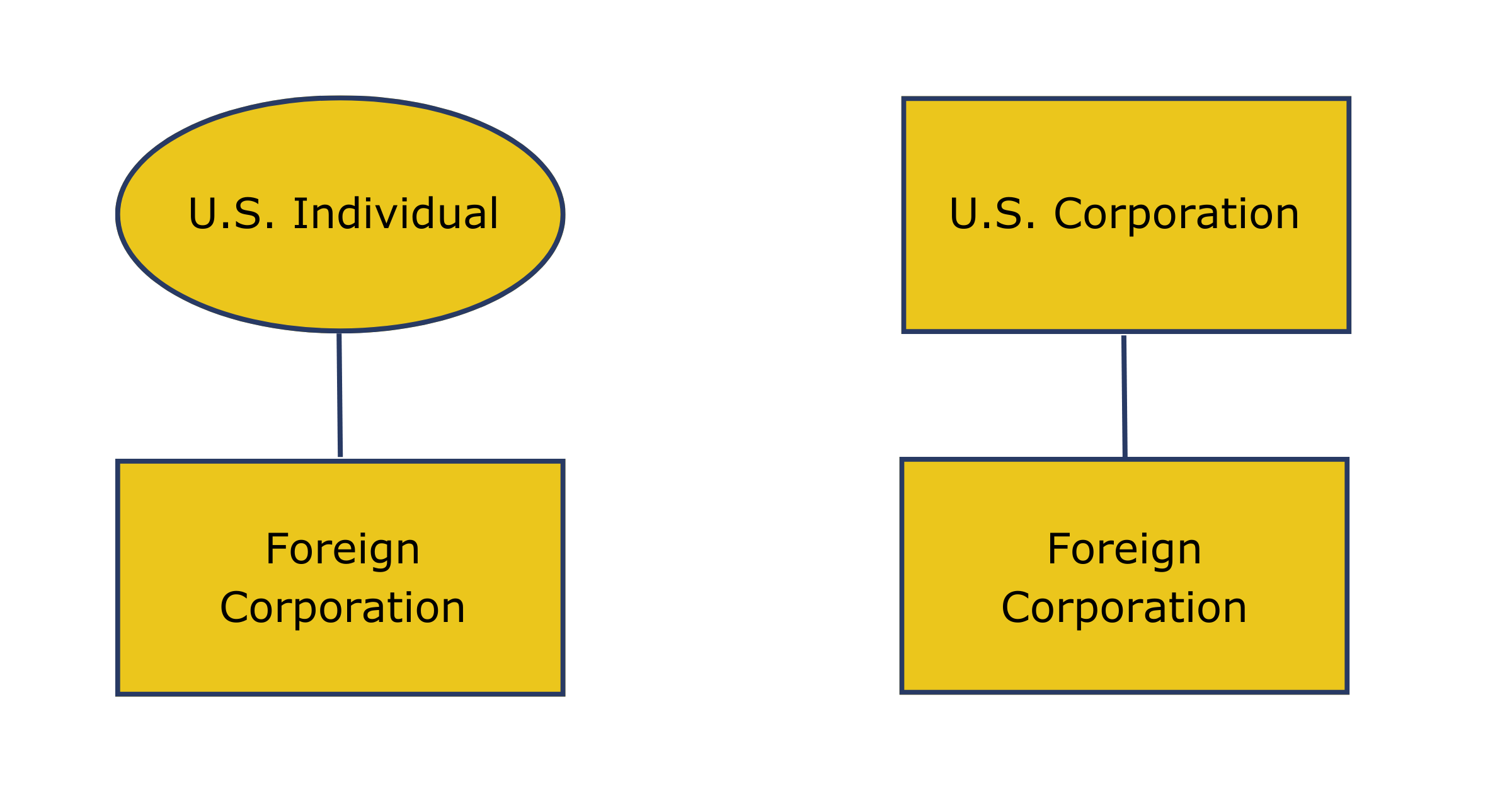

FOREIGN CORPORATION

A U.S. taxpayer may also choose to set up an entity in a foreign country and treat it as a corporation for U.S. tax purposes. Assuming U.S. persons (both individuals and entities) who qualify as U.S. shareholders under the applicable rules collectively own more than 50 percent of the total voting power or the total value of the foreign corporation stock, the company will be considered a controlled foreign corporation (CFC) for U.S. federal income tax purposes. As such, it may be subject to U.S. income tax under either or both of two CFC regimes in the U.S., the familiar Subpart F rules intended to prevent deferral of certain types of income and the relatively new Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income inclusion (commonly referred to as GILTI), a new minimum tax regime introduced with the 2017 U.S. tax reform.

Under the Subpart F anti-deferral regime, certain sales, services income and passive investment income of the CFC may be subject to current U.S. taxation at ordinary income tax rates. With the introduction of GILTI in 2017, the U.S. tax rules now also pull most non-Subpart-F CFC earnings into the U.S. tax net. An elective exception from GILTI may be available for CFC income taxed above an effective tax rate of 18.9 percent.

A corporate U.S. shareholder may take a partial tax credit for foreign taxes paid on earnings included under Subpart F and GILTI. Additionally, domestic corporate shareholders are allowed a deduction (Sec. 250 deduction) which effectively brings the GILTI tax rate down to 10.5 percent (or 13.125 percent starting in 2026) instead of the regular GILTI rate of 21 percent it would otherwise be subject to. These two benefits are not available to individual shareholders unless they make an annual election under Sec. 962, as outlined below.

- Distributions: Since most income of a CFC has likely been subject to tax under Subpart F or GILTI already, actual distributions from the CFC to its U.S. shareholders are generally tax-free up to the amount of earnings and profits that have previously been taxed under GILTI and Subpart F. For distributions exceeding the previously taxed earnings and profits (PTEP), the tax consequences vary depending on whether the U.S. shareholder is an individual or a corporation. If the U.S. shareholder is an individual, the excess distribution will be subject to individual tax as well as the net investment income tax (NIIT). If, however, the U.S. shareholder is a U.S. corporation, then distributions in excess of PTEP may be tax-free.

- While this seems like an unfair outcome in favor of U.S. corporate shareholders, there is a way for individual taxpayers to avail themselves of many of the same benefits as corporate U.S. shareholders. The key to unlocking that benefit is in Internal Revenue Code Section 962, under which individual shareholders may annually elect to be taxed as a domestic corporation with respect to Subpart F and GILTI. With this election in place, U.S. individuals can take a credit for foreign taxes paid by the CFC on its income that is subject to either Subpart F or GILTI, as well as apply the Section 250 deduction in calculating their GILTI inclusion, effectively reducing the U.S. tax rate on GILTI.

- Tax Compliance: The rules themselves are quite complex, and so are the tax forms required to report all of this on a U.S. taxpayer’s annual federal income tax return. Forms 5471 and 8992 need to be filed to report the earnings. Subpart F and GILTI for a CFC are significantly more involved than the required tax reporting for a foreign branch or an FDE and require much more detailed information and recordkeeping to track required information. This increases the administrative burden and the time needed to prepare the necessary U.S. tax forms.

- Other Considerations: While the 2017 U.S. tax reform was ostensibly intended to create a territorial tax regime, the reality is that GILTI has become a “catch-all” minimum tax framework that imposes U.S. tax on most of a CFC’s non-Subpart-F income. The mechanics of the rules are complex, and unless an exception applies, a CFC’s earnings are now generally taxable to the U.S. shareholder in the year earned, albeit in some cases at a preferential U.S. tax rate.

SUMMARY: COMPARING INTERNATIONAL ENTITY TYPES |

||

FOREIGN BRANCH |

FOREIGN DISREGARDED ENTITY |

CONTROLLED FOREIGN CORPORATION |

No legal entity |

Hybrid |

Legal entity |

Simpler U.S. tax compliance |

Simpler U.S. tax compliance |

More time-consuming U.S. compliance |

Easy repatriation |

Easy repatriation |

Potential tax on distributions (and NIIT for individual taxpayers) |

Foreign tax credits |

Foreign tax credits |

Foreign tax credits (only with Sec. 962 election for individual taxpayers) |

Fully subject to U.S. income tax at ordinary rate |

Fully subject to U.S. income tax at ordinary rate |

Lower effective tax rate on CFC earnings under GILTI for corporate taxpayers (only with Sec. 962 election for individual taxpayers) |

The rules of setting up a business abroad are complex. Careful planning with a qualified advisor prior to execution is therefore extremely important to ensure that the entity structure supports the business goals in a sustainable and tax-efficient manner.

GHJ’s International Tax Services Practice can discuss available structuring options in detail and advise clients as they grow their business internationally.